Nondeterministic finite automaton

In the automata theory, a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) or nondeterministic finite state machine is a finite state machine where from each state and a given input symbol the automaton may jump into several possible next states. This distinguishes it from the deterministic finite automaton (DFA), where the next possible state is uniquely determined. Although the DFA and NFA have distinct definitions, a NFA can be translated to equivalent DFA using powerset construction, i.e., the constructed DFA and the NFA recognize the same formal language. Both types of automata recognize only regular languages. Nondeterministic finite automata were introduced in 1959 by Michael O. Rabin and Dana Scott,[1] who also showed their equivalence to deterministic finite automata.

Non-deterministic finite state machines are sometimes studied by the name subshifts of finite type. Non-deterministic finite state machines are generalized by probabilistic automata, which assign a probability to each state transition.

Contents |

Informal introduction

An NFA, similar to a DFA, consumes a string of input symbols. For each input symbol it transitions to a new state until all input symbols have been consumed. Unlike a DFA, it is non-deterministic in that, for any input symbol, its next state may be any one of several possible states. Thus, in the formal definition, the next state is an element of the power set of states. This element, itself a set, represents some subset of all possible states to be considered at once. The notion of accepting an input is similar to that for the DFA. When the last input symbol is consumed, the NFA accepts if and only if there is some set of transitions that will take it to an accepting state. Equivalently, it rejects, if, no matter what transitions are applied, it would not end in an accepting state.

An extension of the NFA is the NFA-ε (also known as NFA-λ or the NFA with epsilon moves), which allows a transformation to a new state without consuming any input symbols. Transformations to new states without consuming an input symbol are called ε-transitions or λ-transitions. They are usually labeled with the Greek letter ε or λ. For example, if it is in state 1, with the next input symbol an a, it can move to state 2 without consuming any input symbols, and thus there is an ambiguity: is the system in state 1, or state 2, before consuming the letter a? Because of this ambiguity, it is more convenient to talk of the set of possible states the system may be in. Thus, before consuming letter a, the NFA-epsilon may be in any one of the states out of the set {1,2}. Equivalently, one may imagine that the NFA is in state 1 and 2 'at the same time': and this gives an informal hint of the powerset construction: the DFA equivalent to an NFA is defined as the one that is in the state q={1,2}.

Formal definition

An NFA is represented formally by a 5-tuple, (Q, Σ, Δ, q0, F), consisting of

- a finite set of states Q

- a finite set of input symbols Σ

- a transition relation Δ : Q × Σ → P(Q).

- an initial (or start) state q0 ∈ Q

- a set of states F distinguished as accepting (or final) states F ⊆ Q.

Here, P(Q) denotes the power set of Q. Let w = a1a2 ... an be a word over the alphabet Σ. The automaton M accepts the word w if a sequence of states, r0,r1, ..., rn, exists in Q with the following conditions:

- r0 = q0

- ri+1 ∈ Δ(ri, ai+1), for i = 0, ..., n−1

- rn ∈ F.

In words, the first condition says that the machine starts in the start state q0. The second condition says that given each character of string w, the machine will transition from state to state according to the transition relation Δ. The last condition says that the machine accepts w if the last input of w causes the machine to halt in one of the accepting states. Otherwise, it is said that the automaton rejects the string. The set of strings M accepts is the language recognized by M and this language is denoted by L(M).

For more comprehensive introduction of the formal definition see automata theory.

- NFA-ε

The NFA-ε (also sometimes called NFA-λ or NFA with epsilon moves) replaces the transition function with one that allows the empty string ε as a possible input, so that one has instead

- Δ : Q × (Σ ∪{ε}) → P(Q).

It can be shown that ordinary NFA and NFA-ε are equivalent, in that, given either one, one can construct the other, which recognizes the same language.

Example

Let M be a NFA-ε, with a binary alphabet, that determines if the input contains an even number of 0s or an even number of 1s. Note that 0 occurrences is an even number of occurrences as well.

In formal notation, let M = ({s0, s1, s2, s3, s4}, {0, 1}, Δ, s0, {s1, s3}) where the transition relation T can be defined by this state transition table:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M can be viewed as the union of two DFAs: one with states {S1, S2} and the other with states {S3, S4}. The language of M can be described by the regular language given by this regular expression (1*(01*01*)*) ∪ (0*(10*10*)*). We define M using ε-moves but M can be defined without using ε-moves.

Properties

The machine starts in the specified initial state and reads in a string of symbols from its alphabet. The automaton uses the state transition function Δ to determine the next state using the current state, and the symbol just read or the empty string. However, "the next state of an NFA depends not only on the current input event, but also on an arbitrary number of subsequent input events. Until these subsequent events occur it is not possible to determine which state the machine is in".[2] If, when the automaton has finished reading, it is in an accepting state, the NFA is said to accept the string, otherwise it is said to reject the string.

The set of all strings accepted by an NFA is the language the NFA accepts. This language is a regular language.

For every NFA a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) can be found that accepts the same language. Therefore it is possible to convert an existing NFA into a DFA for the purpose of implementing a (perhaps) simpler machine. This can be performed using the powerset construction, which may lead to an exponential rise in the number of necessary states. A formal proof of the powerset construction is given here.

Properties of NFA-ε

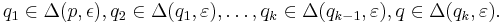

For all  one writes

one writes  if and only if

if and only if  can be reached from

can be reached from  by going along zero or more ε arrows. In other words,

by going along zero or more ε arrows. In other words,  if and only if there exists

if and only if there exists  where

where  such that

such that

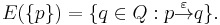

For any  , the set of states that can be reached from p is called the epsilon-closure or ε-closure of p, and is written as

, the set of states that can be reached from p is called the epsilon-closure or ε-closure of p, and is written as

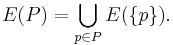

For any subset  , define the ε-closure of P as

, define the ε-closure of P as

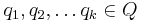

The ε-transitions are transitive, in that it may be shown that, for all  and

and  , if

, if  and

and  , then

, then  .

.

Similarly, if  and

and  then

then

Let x be a string over the alphabet Σ∪{ε}. An NFA-ε M accepts the string x if there exist both a representation of x of the form x1x2 ... xn, where xi ∈ (Σ ∪{ε}), and a sequence of states p0,p1, ..., pn, where pi ∈ Q, meeting the following conditions:

- p0

E({q0})

E({q0}) - pi

E(T(pi−1, xi)) for i = 1, ..., n

E(T(pi−1, xi)) for i = 1, ..., n - pn ∈ F.

Implementation

There are many ways to implement a NFA:

- Convert to the equivalent DFA. In some cases this may cause exponential blowup in the size of the automaton and thus auxiliary space proportional to the number of states in the NFA (as storage of the state value requires at most one bit for every state in the NFA)[3]

- Keep a set data structure of all states which the machine might currently be in. On the consumption of the last input symbol, if one of these states is a final state, the machine accepts the string. In the worst case, this may require auxiliary space proportional to the number of states in the NFA; if the set structure uses one bit per NFA state, then this solution is exactly equivalent to the above.

- Create multiple copies. For each n way decision, the NFA creates up to

copies of the machine. Each will enter a separate state. If, upon consuming the last input symbol, at least one copy of the NFA is in the accepting state, the NFA will accept. (This, too, requires linear storage with respect to the number of NFA states, as there can be one machine for every NFA state.)

copies of the machine. Each will enter a separate state. If, upon consuming the last input symbol, at least one copy of the NFA is in the accepting state, the NFA will accept. (This, too, requires linear storage with respect to the number of NFA states, as there can be one machine for every NFA state.) - Explicitly propagate tokens through the transition structure of the NFA and match whenever a token reaches the final state. This is sometimes useful when the NFA should encode additional context about the events that triggered the transition. (For an implementation that uses this technique to keep track of object references have a look at Tracematches.[4])

Application of NFA-ε

NFAs and DFAs are equivalent in that if a language is recognized by an NFA, it is also recognized by a DFA and vice versa. The establishment of such equivalence is important and useful. It is useful because constructing an NFA to recognize a given language is sometimes much easier than constructing a DFA for that language. It is important because NFAs can be used to reduce the complexity of the mathematical work required to establish many important properties in the theory of computation. For example, it is much easier to prove the following properties using NFAs than DFAs:

- The union of two regular languages is regular.

- The concatenation of two regular languages is regular.

- The Kleene closure of a regular language is regular.

Notes

- ^ Rabin and Scott (1959)

- ^ FOLDOC Free Online Dictionary of Computing, Finite State Machine

- ^ http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~ccalabro/essays/fsa.pdf

- ^ Allan, C., Avgustinov, P., Christensen, A. S., Hendren, L., Kuzins, S., Lhoták, O., de Moor, O., Sereni, D., Sittampalam, G., and Tibble, J. 2005. Adding trace matching with free variables to AspectJ. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Object Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications (San Diego, CA, USA, October 16–20, 2005). OOPSLA '05. ACM, New York, NY, 345-364.

References

- M. O. Rabin and D. Scott, "Finite Automata and their Decision Problems", IBM Journal of Research and Development, 3:2 (1959) pp. 115–125.

- Michael Sipser, Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS, Boston. 1997. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. (see section 1.2: Nondeterminism, pp.47–63.)

- John E. Hopcroft and Jeffrey D. Ullman, Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading Massachusetts, 1979. ISBN 0-201-02988-X. (See chapter 2.)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||